- Home

- Ian Roberts

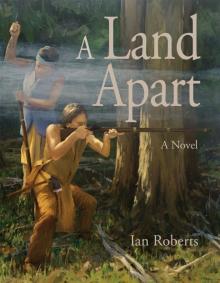

A Land Apart

A Land Apart Read online

Copyright © 2019 by Ian Roberts

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Roberts, Ian, 1952 - author.

Title: A land apart / Ian Roberts.

Description: Los Angeles: Atelier Saint-Luc Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018902867 | ISBN 978-0-9728723-3-1 (pbk.) | ISBN 978-0-9728723-4-8 (Kindle ebook) | ISBN 978-0-9728723-8-6 (EPUB ebook) | 978-0-9728723-9-3 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Bru 1 -1632—Fiction. | Canada—History—To 1763 (New France)— Fiction. | Europe—Colonies—America—Fiction. | Wyandot Indians—Fiction. | Iroquois Indians— Fiction. | Historical fiction.

BISAC: FICTION / Historical / General. | FICTION / Native American & Aboriginal

GSAFD: Historical Fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3618.034 L36 2019 (print) | LCC PS3618 034 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23

Published by Atelier Saint-Luc Press

200 South Barrington, #202

Los Angeles, CA 90049

Atelier Saint-Luc Press titles are distributed by Small Press United, Chicago (800-888-4741)

Printed in the United States of America.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the Land — that ancient, speaking presence.

New France

1634

Part One

He strokes his fingers along the polished mahogany stock of the musket, caressing it slowly, the way a more sensual man might caress the skin of a lover. His hand curls around the cool black wrought iron of the barrel. The oil on the metal smells sweet. He hoists the musket to his shoulder, pulling the stock in tight as he had been instructed. Sighting down the barrel, he sees only wide-open lake. Slowly he pivots toward land. As the muzzle swings toward them, the English traders duck and scatter out of the way. The soldiers, standing to one side, anxiously raise their own guns in self-defense. Totiri ignores them all.

Staring down the barrel of the musket at a tree trunk several yards away, he pulls the stock in tight again, holds the barrel steady and slowly squeezes the trigger. The flintlock releases with a click and then three powerful, exhilarating sensations hit him at once: the kick of the musket hard into his shoulder, the deafening roar, and the dense, acrid smell of burnt powder smoke. The musket ball strikes the tree as the crashing echo of his shot rolls back from across the lake.

Slowly and carefully, the Iroquois war chief lowers the gun. Never has he experienced such a powerful sensory affront. He revels in its sheer intensity as he slowly regains his equilibrium. Totiri knew before lifting the musket that he wanted it; now the desire consumes him. He holds the musket tight in his grip, unsure what this power is, unsettled by it, knowing only that he is awed by its dark spirit. He looks up, suddenly aware once again of his surroundings. And the English, and his reason for being here — to trade furs for this thundermaker he now holds. But Totiri knows they’ve seen his lust. That is not good. That is weakness.

A British soldier leans towards a comrade, his eyes and musket at the ready, “Like baring your neck to wolves.” His friend nods, aware of the tenuous and dangerous alliance they now forge. “I do not see any good coming from this.”

Handing the gun to an Iroquois warrior beside him, Totiri turns his attention to the English trader. The tension between them is palpable. Totiri eyes the long, wooden cases filled with guns. And several more cases laying behind the traders. He wants them all. He nods at the furs his hunters have brought. The trader flips the furs with a dismissive gesture, implying their inferior quality.

Totiri snarls at the insult. The trader steps back, cringing despite himself, at the intensity of the man’s anger. He has never encountered anyone like Totiri. The war chief bristles with a current of menace and cruelty. Battle scars cover his arms and chest. The trader knows he has the upper hand; he knows how much the Iroquois crave these muskets. He knows he mustn’t back down, holding the war chief’s gaze as long as he can. But he soon folds, unable to withstand the chilling hostility any longer.

This is barter and the trader knows he’s losing. He adds two more kegs of powder and several boxes of shot. He tries to smile, but his fear betrays him, a line of cold sweat runs down the inside of his shirt, another down his forehead into his eyes. Totiri takes him in with undisguised scorn. Then, with the slightest hint of a nod from the chief, his warriors move toward the muskets, powder and shot. The six English soldiers hold their guns loosely at the ready, sensing the danger of the Iroquois suddenly as a group moving toward them. Totiri eyes each case and crate and when the last one passes, he casts a long, last look at the remaining cases behind the traders.

As the last Iroquois turns to go, one of the traders suddenly crosses his path, quietly handing him a small bottle of dark liquid. It is a movement Totiri does not miss. With two swift strides he grabs the bottle, pitches and smashes it on the rocks and strikes the warrior hard across the face with the backhand motion of his throw. As the trader stumbles backwards onto the ground, six soldiers raise their guns at the war chief. Totiri slowly lifts his gaze, staring with disdain straight into their muskets. He knows they wouldn’t dare. He turns his back and walks with a deliberate, slow pace away from the white men, relishing their discomfort. He can smell it.

Four canoes of Wendat return, heavily laden with furs traded with tribes to the west.

In the stern of the last canoe sits a Frenchman, the only white man who has ever ventured this deep into the wilderness, though little in his demeanor or appearance betrays those European roots. Etienne Brulé is about forty years old, with long hair, clean-shaven face, and deerskin vest and leggings. He looks as Wendat as his companions, at least to any European, except for his clear blue eyes. Scars from burns mark almost every inch of his neck and chest.

Paddling in front of Brulé is his friend, Savignon, a Wendat of about the same age. He spent three years in France and it changed him dramatically. Although over twenty years ago some of that European influence is still evident even now in the French smock coat he wears, once a pale grey velvet, though now soiled, discoloured with both sleeves cut off.

As they cross the clearing at the top of the portage, a breathtaking panorama opens up. In the afternoon light, the lake, like beaten gold, appears and reappears off into the distance. The two men stop, two tiny figures in a vast wilderness.

Brulé drops his pack, and slowly spreads his arms wide, breathing in the whole vista of the land before them, as if to embrace it into himself. He turns to Savignon, “This, my friend, is paradise.”

No sooner are the words uttered than the silence is suddenly shattered by the ricocheting, piercing sound of a dozen gunshots.

Gunshots! Brulé gasps at Savignon in horror. The other Wendat stop, frozen. They have no idea what has just happened. The nearest guns, the weapon of the white man, would be more than seven hundred miles away.

Smoke drifts out from behind a point of land far down the lake.

Brulé, Savignon and their Wendat companions run, almost glide, through the woods. They make no sound as they close in to where the gunfire must have come from. They can hear cries and shouts as they carefully make their way to a clearing by the water’s edge.

On that silent sliver of shoreline lie a number of dead warriors. Smoke hangs over the clearing, and the burnt and scattered remains of their small fishing camp still smolder. Brulé looks up from the ravaged scene. Out on the water, Iroquois paddle away, their canoes riding low, crammed with the women and children of the dead men lying before them. The captives’ cries and

wails slowly fade as their canoes, one by one, round the next point of land and disappear down the lake.

No one utters a word. Never before has a Wendat seen a man killed by a bullet. Scanning the slaughter, Brulé pieces together what must have happened. The Iroquois had arrived silently through the woods and surrounded the camp. Then fired. Each warrior dropped where he had stood. Four men lay in the shallow water by the shore. Three must have still been alive where they fell. They had been given a final deathblow. Two had taken the first bullet and charged but were dropped with the one that followed. The attack would have been over in seconds.

Savignon turns over one of the warriors. “Chippawa,” he says. “Iroquois allies. We have never had Iroquois this far west before.”

Brulé nod, “For them to do this, to their allies, the Iroquois must hurt from the white man’s disease more than we realize. More than it hurts us,” adds Brulé.

A slight stirring behind them breaks the silence. As one, the Wendat turn, alert, clubs and tomahawks raised and ready. Brulé, standing to one side of his companions, realizes what has drawn their attention and relaxes. He calls out, “Hey, little man. You need not fear us.”

Nothing moves. He tries again. “We will get you home. You cannot stay here.”

From behind a tree, the frightened face of a young boy peers out. Brulé gestures to him to approach, holding out his hand. No more than four or five, tear-stained, dirty and almost naked, the boy slowly steps into the clearing. A bullet has grazed his side and a wide stream of blood flows from his wound snaking its way down his leg. Tentatively, he moves towards Brulé’s outstretched hand. The white man pulls him gently to his side, resting his hand on the boy’s head. He looks at the silent, grim faces of his Wendat companions.

Samuel Champlain, the Governor of New France, taps his finger slowly and methodically on his desk. He stares at the sunlight gently streaming through the small window of his office. Two men lean against the heavy timber wall of the fort, smoking their pipes in the morning sun.

Champlain is sixty-years-old and looks it. Wresting Québec into existence has taken its toll. For the last twenty-five years he has devoted his life to fashioning this tiny colony out of a brutal, uncooperative wilderness. Although New France in principle stretches over a territory fifteen times the size of France itself, it is only here in Québec that some semblance of colonization has slowly taken root.

Each year the promise of land and its riches draws the adventurers and dreamers out of France. One winter here and most beg to return home. Yet, the French government, despite all evidence to the contrary, stubbornly continues to believe that Québec will yield the kind of riches Spain discovered in their New World to the south.

Champlain can never quite anticipate what will arrive each summer with the supply ships that come from France once a year. But always when they discharge their cargo they also discharge new plans, new demands, or even a new governor to replace him — until the grim reality of running this place sets in and the newly-arrived find any excuse to head back. The French court, when they think of New France at all, envisions turning this wilderness into a kind of frontier Paris. Unlike them, he has learned through long experience here to temper his expectations.

When young, Champlain had spent time with the Spanish in the Caribbean and had seen the misery inflicted on the native people — not just the slavery but the pillage and murder. He had vowed to do things differently here in New France. He believed the French could live with the natives as one, in peace, assuming, of course, that they would live as one as Christians.

The Algonquin, the tribe living in the vicinity of Québec, had forced him however to reconsider his assumptions and expectations of both the land, and its people. Even if he didn’t understand them, he had come to admire much about the native people. And he admits now, to himself, that his efforts to convert them to Christianity have only weakened and confused them. This has been his most bitter realization and personal trial. At times, it plagues him and shakes his convictions to their core. What is he really doing here? Who and what, in the end, is he serving?

Before him now, yet one more time, sits another new agent sent by Cardinal Richelieu to hurry things along. Champlain has not been with him five minutes and already he detests the man. Father du Barre, the new Jesuit superior assigned to New France, arrived a day ago on the supply ships.

He can already see that du Barre, with his naive, misguided enthusiasm, will lord the rigid structures of his Catholic convictions over the Algonquin and Québec and smother the colony, until…well, until what?

Champlain pulls his gaze from the view out the window, back to the du Barre sitting across from him, to the priest’s thin white face, carefully cropped black beard and the meticulous elegance of his black robe. Slowly and repeatedly turning the finely crafted silver and ivory crucifix in his hand, he exudes a confident impenetrability, alerting Champlain to what he knows will be impractical and time-consuming nonsense.

Du Barre, ever so piously and humbly, has been taking pains to describe his position in court and most importantly, his relationship to Cardinal Richelieu. Despite himself, Champlain’s attention has drifted off. A sudden silence draws him back; du Barre has stopped speaking. Champlain scrutinizes the priest, and suddenly realizes who this man reminds him of, in fact who he models himself after: Father Joseph, l’Eminence Grise, that terrifyingly powerful and ruthless Capuchin monk, advisor to Richelieu. He also realizes he has offended the man and if he is anything like Father Joseph, he must be careful. He knows he has inadvertently created tension between them and must now work to bridge it.

“Sorry, Father du Barre. So why has the good Cardinal sent you here?”

“I was saying, His Eminence does not wish to lose New France again.”

“We received no supply ships for over two years. We were a week away from starvation. All of us.”

Nothing makes Champlain as angry as the insinuation that somehow he had lost New France while France had been at war with England. France had in fact abandoned Québec, desperately overextended on the home front. And the English had simply seized the opportunity. With no supplies or munitions from France for over two years, Champlain had been forced to surrender. When the war ended later that same year, New France was returned by treaty. Yet even now, Richelieu continues to blame Champlain. Du Barre dismisses Champlain’s agitation with a regal turn of his hand.

“The English are pushing further north and west from their colonies—”

“As I have been reporting for years.”

Du Barre eyes Champlain sharply, then continues, “— and Cardinal Richelieu wishes to create a new colony strategic to keeping the flow of furs to France for the long term. A new colony east of here, well-fortified, to stop this move of the English north.”

“The English have created an uneasy alliance with the Iroquois,” says Champlian. “I strongly recommended several years ago, in one of my several reports, that it would be strategically wise to build a second colony at Trois-Rivières with a well-garrisoned fort between us at Ile Saint Croix. We could defend a colony there, and the growing season is longer — another advantage.”

The priest continues as though Champlain hasn’t spoken. “In exchange for all trading rights in New France, the new Company of One Hundred Associates has agreed to fund four thousand settlers over fifteen years. Three hundred a year. Each new colonist will be sponsored for three years.”

Champlain raises his eyes in disbelief at the audacity of these numbers — three hundred a year! It’s hopelessly unrealistic. But he is careful to watch his words, choosing to reply with one simple fact so he doesn’t appear to be over-reacting and offend the priest yet further.

“We have been here twenty-five years and do not yet have two hundred settlers in Québec.”

“You can be sure His Eminence is aware of your success here,” du Barre responds.

Champlain can feel his cheeks burning at the priest’s implied rebuke. After trying

for so long to gain support for New France, to convince the court of the colony’s value, this was indeed glorious news. It is in fact a vindication of his years of fostering and promotion. But the way in which du Barre delivers the news infuriates him. He stares at the priest, speechless. If the man stays, what, he wonders, if anything, would strip him of this pious superiority? Where is the chink in his formidable armour? He had seen this land strip men bare over and over again and without much mercy.

Du Barre continues. “Cardinal Richelieu is making a huge financial commitment to this. In return, he will need to see real profits, returned to France, not only to Québec. We would expand the fur trade. We believe we can find gold and silver here much as the Spanish have found to the south. And we will look for a route to the Indies.”

Champlain holds up his hand and opens his mouth to reply, then slumps back in his chair. France, yet again, has sent another emissary of futility.

“You propose a fantasy. We have never found gold or silver. Nor have the natives or they would have brought it to us because they know we look for it. And there is no route to the Indies.”

“The land cannot go on forever.”

“Perhaps, but you travel this land in canoes, not trading ships. We know what lies over a thousand miles west of here and from the reports of the tribes there, what lies another five hundred miles west of that.”

Du Barre’s eyes narrow. “How do you know that?” Champlain hesitates, anticipating exactly what du Barre will bring up next.

“This Brulé,” du Barre almost spits out the name, and Champlain sags a little more in his chair realizing just how predictably this conversation will unfold. “Do you truly believe this trade arrangement you have with him for furs best serves the interests of France?”

A Land Apart

A Land Apart